Using a 3D printing prototype service can feel like a shortcut to innovation, but the process is rarely plug-and-play. Many teams rush into it expecting perfect results, only to hit delays, wasted budgets, or unusable parts. Prototyping works best when treated as a learning phase, not a final destination. Understanding where others go wrong helps you ask better questions, make smarter decisions, and turn rough ideas into functional, testable products without unnecessary friction.

1. Treating the Prototype Like a Final Product

One of the most common miscalculations is awaiting prototype corridors to bear like product-ready factors. Prototypes are trials, not polished issues. When teams judge face finish, strength, or lifetime too roughly at this stage, they miss the real value. The thing is to validate form, fit, and function. Pushing for perfection too beforehand frequently inflates costs and slows progress. Smart teams let prototypes stay amiss while learning what truly matters.

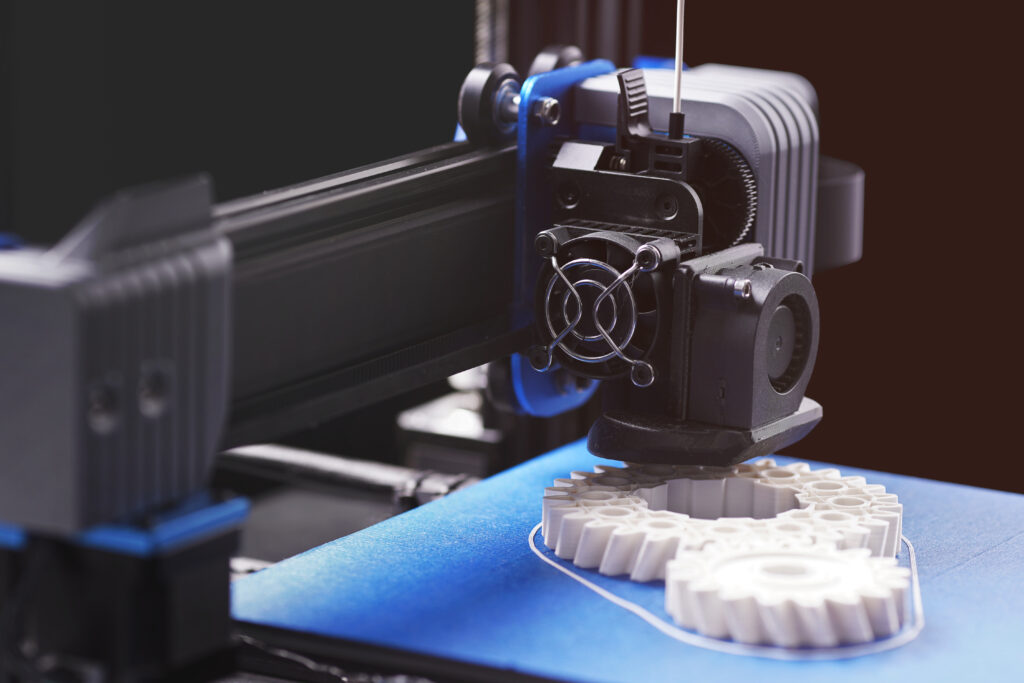

2. Choosing the Wrong Printing Technology

Not all 3D printing styles are exchangeable, yet numerous people assume they are. FDM, SLA, SLS, and essence printing all bear else under stress, heat, and cargo. Picking a process without understanding its limits can lead to deceiving test results. A prototype that cracks or foundations may not be a bad design, just a poor technology match. Time spent aligning the system with the use case saves frustration later.

3. Ignoring Material Behavior Early On

Material choice is n’t just about color or cost. Different plastics and resins respond uniquely to impact, temperature, and repeated use. Overlooking this can produce false confidence or gratuitous fear during testing. A brittle prototype might scarify stakeholders indeed though the product material would perform well. Understanding how published accoutrements differ from final accoutrements helps you interpret results directly rather than overreacting to anticipated limitations.

4. Sending Unrefined or Incomplete CAD Files

A rushed CAD train frequently leads to rushed problems. Small modeling crimes, unsubstantiated features, or unrealistic forbearance can beget prints to fail or bear repeated variations. Numerous assume the service provider will “ fix it, ” but that infrequently happens without redundant cost. Taking time to review figure, wall consistency, and assembly concurrences before submission reduces back- and- forth. Clean lines do n’t guarantee success, but messy bones nearly guarantee detainments.

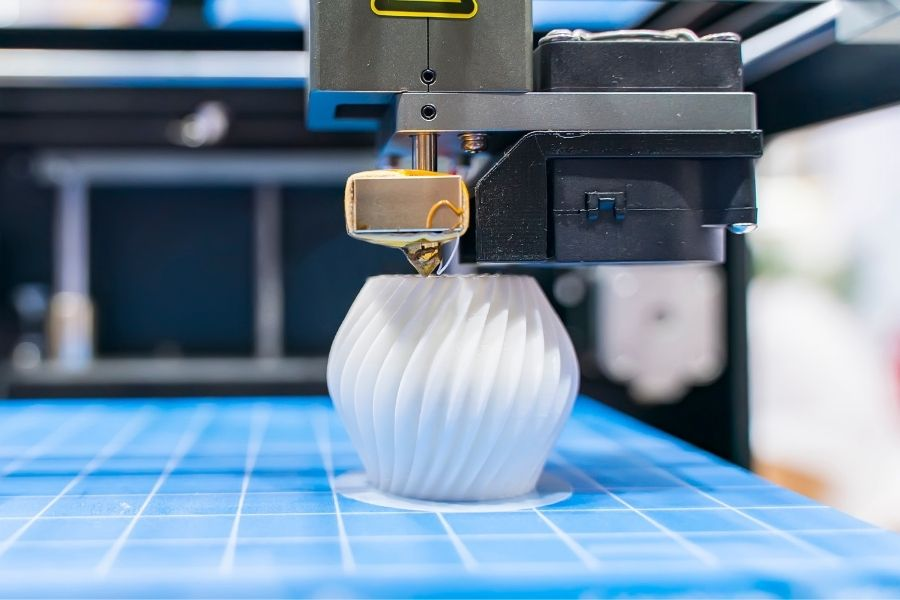

5. Underestimating Post-Processing Needs

Raw published corridors infrequently come off the machine ready for testing or donation. grinding, curing, support junking, and face finishing all take time. teams frequently forget to regard this when planning timelines. That oversight can fail meetings or demonstrations. Understanding post-processing conditions outspokenly helps set realistic schedules. It also avoids disappointment when a part looks rough straight out of the printer, which is fully normal.

6. Failing to Communicate the Prototype’s Purpose

Not all prototypes serve the same thing. Some are for visual feedback, others for mechanical testing, and some for investor demonstrations. When that purpose is n’t easily communicated, the service provider may optimize for the wrong thing. A visually perfect model might be too fragile for functional tests. Clear intent attendants opinions around resolution, accoutrements , and homestretches, icing the prototype actually answers the questions it was meant to explore.

7. Assuming Speed Always Equals Efficiency

Fast reversal is tempting, but rushing every replication frequently backfires. Quick prints without reflection can pile up unused corridors and confusion. Prototyping works best in cycles that include review and adaptation. decelerating down slightly between duplications allows perceptivity to settle and design advancements to crop . Speed is precious, but only when paired with literacy. Otherwise, it becomes a precious stir without meaningful progress.

8. Overlooking Tolerances and Assembly Fit

numerous first- time users are surprised when corridors that look perfect on screen do n’t fit together in real life. 3D printing has essential forbearance, and ignoring them causes misalignment or weak joints. Assemblies bear purposeful gaps and allowances. Testing individual factors without considering how they interact can hide problems until late stages. Early attention to fit saves painful redesigns when multiple corridors eventually come together.

9. Not Budgeting for Iteration and Failure

Prototyping without awaiting failure is a form of frustration. Some prints will fail. Some designs wo n’t work. That’s not wasted plutocrat; it’s the cost of literacy. teams that budget only for “ success ” frequently horrify when effects go wrong. Erecting fiscal and emotional room for replication makes the process healthier. Failure beforehand, in small ways, prevents much larger failures after launch.

10. Relying Too Heavily on the Service Provider

A prototype service is a partner, not a replacement for internal thinking. Expecting them to make design decisions or catch every issue shifts responsibility the wrong way. The most successful projects involve collaboration, not delegation. Asking questions, reviewing results critically, and staying involved leads to better outcomes. When teams stay engaged, the prototype becomes a shared learning tool rather than a black box output.

Conclusion

Using 3D printing wisely means respecting its strengths and limits. Avoiding these common mistakes keeps prototypes focused on learning, not perfection. When treated as part of a larger development strategy, prototyping accelerates smarter decisions and smoother launches. Teams that combine thoughtful iteration with clear goals are better positioned to move from concept to market, especially when supported by a capable product launch agency.